“The Museum of Lost Art”: Examining the vulnerability of the world’s treasures

“The Museum of Lost Art”: Examining the vulnerability of the world’s treasures

Carolyn Riccardelli will never forget the day in 2002 when a sculpture named Adam took a terrible fall. The conservator for the Metropolitan Museum of Art says the 6-foot-3-inch “Adam” was gravely damaged after his plywood pedestal buckled.

“I went upstairs and I saw the sculpture in pieces all over the floor. … He was in 28 large pieces and hundreds of small pieces,” Riccardelli told CBS News’ Dana Jacobson.

“This is one of the most important sculptures from the early Renaissance. Certainly in the western hemisphere outside of Italy. And when something like this breaks, we couldn’t accept the loss,” she said.

“Adam” is one of the pieces author and art historian Noah Charney examined in his new book about the vulnerability of the world’s treasures, “The Museum of Lost Art.” How big would a museum of lost art be? Charney says “bigger than all the museums of the world combined.”

“It would have works by every artist you’ve heard of because there really isn’t an artist to exist who doesn’t have works that are lost,” Charney said.

Some lost works are due to theft, like the 13 masterpieces snatched from Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1990. The stolen art is valued at around half a billion dollars and included a Rembrandt and Vermeer.

“The theft from the Gardner museum took place on St. Patrick’s Day night. And two people dressed as policemen knocked on the employee entrance and against regulations the security guards that night let them in. The security guards were seized and tied up and gagged and put down in the basement and for about 40 minutes these two thieves went through the museum and they took 13 objects. They stomped on certain works of art that suggests that they were sort of oblivious to their value but they were very careful with others and those works have never been found again. It’s the big mystery there’s many detectives proactively looking for. There’s a $5 million reward if you happen to know where they are and it’s a thorn in the side of the FBI and the investigators because it’s been an open case for so long,” Charney said.

“Few people realize that art that has been called the third highest grossing criminal trade worldwide behind only the drug and arms trade. It’s absolutely enormous and by far the biggest problem is illicit trade in antiquities and that’s been highlighted in 2015 since it’s been overtly clear that ISIS was making a lot of money by selling looted antiquities. So it also funds terrorism. So whether or not you’re an art lover it’s important to take it seriously,” Charney said.

Long before ISIS, there were other wartime villains far worse, according to Charney.

“Napoleon, who was the first to organize a special unit of his army that was dedicated to stealing art and to require when you had an armistice signing him with him when he stopped shooting at you, you have to give him some of your art as payment. But the Nazis were the biggest bad guys. An estimated five million cultural heritage objects changed hands inappropriately during the second World War and many thousands of them are still lost,” he said.

Others have been recovered, including some that were hidden in plain sight like Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi. It was purchased for 45 pounds in 1958 but nearly 60 years later would become the most expensive painting ever sold at auction.

“It was sold for $450 million and that’s because it was misidentified as a 19th century pastiche based on a lost Leonardo and it was very dirty and had to be cleaned, provenance research had to be done to make sure it was the real thing. And then all of a sudden the value skyrockets and there are countless stories like this and each one is this beautiful shining diamond in the sand that you spot and you cross your fingers that it’s the real deal but it inspires hope that many of the works that we think are lost for good might be found again,” Charney said. “The problem is that a lot of luck is involved. So you can follow trails but so much of it is buried and has to be buried in organized archaeological expeditions or by chance which can happen sometimes and you have to stare very carefully at what’s hidden in your attic or in a dark corner of your house because you might just have something very precious there.”

Technology, like luck, can also play a role. Using the latest advancements in detection, works we never knew existed by artists like Goya, Picasso and Malevich have been uncovered.

“And one of the ways that they can find lost works is by using a different light spectra to look behind the surface of works of art and there’s these examples of very surprising discoveries like Kazimir Malevich black square which is one of the most famous paintings. Turns out there are two paintings buried underneath it and looking at it with special light spectra that lets you look beneath the surface allows you to not harm the painting itself but to see what’s lying beneath,” Charney said.

And for priceless pieces that suffer damage, like Adam, resurrection can be possible with years of painstaking work.

“The most credit has to go to the conservators not only for their technical skill but for the fact that they didn’t give up on something that was in hundreds of splinters where you might throw up your hands and say it’s a lost cause but now it looks as good as new,” Charney.

Jakarta’s Museum MACAN: No damaged Yayoi Kusama artworks, or special treatment for influencers

Jakarta’s Museum MACAN: No damaged Yayoi Kusama artworks, or special treatment for influencers

A director at Jakarta’s Museum MACAN said none of Yayoi Kusama’s artworks were damaged by visitors touching, moving or taking selfies with them, despite someone partially rubbing out one of her famous polka dots.

The Jakarta Globe previously ran an article that sparked a lot of debate about selfie-taking and damaged artworks at Museum MACAN.

However, during a meeting with museum director Aaron Seeto on May 24, he confirmed that no artworks had been damaged.

“I can confirm that no artworks had been damaged by visitors to the museum. What was reported was actually inaccurate and the images were posted by a volunteer, not a staff member,” he said.

He added that the photos, which he described as inaccurate and out of context, were not authorized by the museum.

The previous story, published on May 18, was based on a series of photos Amanda Aulia, a part-time staff member at Museum MACAN, posted on her Instagram account @amansaulia on May 17, showing damage to Kusama’s artworks.

“Unfortunately, I am not going to respond to the motives of another person, especially in distributing something that was not authorized by the museum,” Seeto said.

He went through some photos and explained the condition of the artworks.

Seeto said the partially erased polka dot was actually a replaceable sticker and that the museum had expected a huge turnout, so there was scheduled maintenance to replace those stickers.

“So the stickers in the image that was reported were actually replaceable, and that image was taken before our maintenance teams were able to go through,” he said.

Regarding one of the silver balls in Narcissus Garden, Seeto said it had been “dislodged” but that the artwork was not damaged.

Entang Wiharso’s plexiglass paintings in the Children’s Artspace, on the other hand, are allowed to be touched.

“In the children’s art space, Entang’s artwork is actually designed for young children to understand how artists create. So there are components kids may touch and again, from time to time we have to maintain the artwork. They are allowed to touch that work, so from time to time, we only need to change it,” he said.

He reiterated that the images that went viral on social media were taken and distributed by the volunteer before the scheduled maintenance could take place.

“I have a conservator on board. We do a daily review of the exhibition. We all have the planning in place, the planning is part of the design of the exhibition and the images you have seen are all of the works that have interactive elements. And we know that we have processes to maintain the artworks and these images were taken before our team was able to maintain the artwork.”

Did influencers cause trouble?

The Jakarta Globe’s article originally featured two photos of Instagram influencers seen mistreating the artwork.

One was seen sitting on the kitchen counter in Obliteration Room. When writing the article, Museum MACAN communications officer Nina Hidayat told the Globe that sitting is only allowed in the chairs, because going to the room “is like visiting someone’s house.”

Seeto expressed a similar sentiment.

“They are able to sit on certain parts of the installation. We prefer people not to sit on the counters, but again, the artwork was not damaged.”

The other photo depicted a man leaning on one of Kusama’s pieces titled Dots Obsessions. The owner of the photo, who goes by the name Abi Shihab, clarified that he was not leaning on the artwork, as it is made from soft material and cannot support his weight.

He said he used his feet to support his body, and the lighting made it look like there was no distance between him and the artwork.

However, Seeto declined to specifically comment on this picture.

“Of course, there are things people can’t do and they are instructed not to do. Touching a certain element is not permitted and from time to time, people touch it and we prefer that they don’t. From time to time, people do touch artwork and we prefer that they do not and there are rules and guidelines in place for people to not to touch the works.

“I can’t comment on the picture and I think my response is very clear that no artworks were damaged here. Our team and visitors are also instructed on how to behave inside the museum but I am not commenting on the image,” he said.

Seeto said influencers do not get preferential treatment but prior to the public opening of the exhibition, there had been several previews to which members of the media, sponsors, influencers and MACAN Society members were invited. However, there are no different rules regarding their interaction with the artworks.

“During the preview days, we had all kinds of interested people coming to the exhibition. There were artists — young artists, established artists — curators, architects, fashion designers, media people so that the assumption that only influencers attended the exhibition is not actually the full picture,” he said.

He added that after an exhibition opened to the public, the museum welcomed people from all backgrounds. On weekends, they mostly dealt with families. The museum also hosted a sponsored school visit on the day of the interview.

Maintenance

Since the museum is open to everyone of any age, Seeto said there are protocols in place to protect artworks, such as selling timed tickets to limit visitor traffic, having 24-hour security, making sure that children are accompanied by adults, and only allowing phone cameras, except for accredited media.

“All of the exhibition design has been thought through very carefully to ensure that the flow of the audience past the artworks that allow participation is managed in a particular way,” Seeto said. — The Jakarta Globe

ICE and DOJ return Christopher Columbus letter to Spain

https://www.ice.gov/news/releases/ice-and-doj-return-christopher-columbus-letter-spain

ICE and DOJ return Christopher Columbus letter to Spain

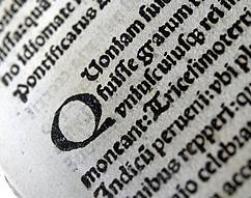

WASHINGTON — Today, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) returned a more than 500-year-old copy of Christopher Columbus’ letter describing his discoveries in the Americas to Spain during an evening repatriation ceremony at the Residence of the Spanish Ambassador to the United States. The letter, originally written in 1493, was stolen from the National Library of Catalonia in Barcelona and sold for approximately $1 million.

The return of the letter was the culmination of a seven-year investigation jointly conducted by ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) and the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Delaware. It began in 2011 when HSI Wilmington (Del.) and the Delaware U.S. Attorney’s Office received a tip that several 15th century original manually printed copies of the Columbus Letter were stolen from European libraries and replaced with forgeries without the knowledge of library officials or local law enforcement. The investigation determined that the stolen Columbus Letter from Spain was sold in November 2005 for 600,000 Euros by two Italian book dealers.

In June 2012, a subject matter expert, accompanied by an HSI Wilmington Special Agent, visited the National Library of Catalonia in Barcelona and reviewed the Columbus Letter in the possession of the library at which time it was determined, in coordination with Spanish authorities and with support from HSI Madrid that the letter at the library was a forgery.

In March 2013, it was discovered that the Columbus Letter believed to have been stolen from Barcelona was reportedly sold for 900,000 euros in June 2011. Following extensive negotiations with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Delaware, the individual in possession of the letter volunteered to transfer custody to HSI Special Agents, which was then brought to Wilmington, Delaware in February 2014 for further examination. In March 2014, a subject matter expert evaluated the letter and determined that the document was “beyond all doubt” the original stolen from the National Library of Catalonia. Additionally, other experts conducted a series of non-invasive digital imaging tests, which determined, among other things, the probable use of a chemical agent to bleach the ink of National Library of Catalonia’s stamp and that the paper fibers of the Catalonia Plannck II Columbus Letter had been disturbed from their original state where the stamps were previously located.

U.S. Attorney David C. Weiss stated, “The recovery of this Plannck II Columbus Letter on behalf of the Spanish government exemplifies not only the significance of federal agency partnerships in these complicated investigations but the close coordination that exists between American and foreign law enforcement agencies. We are truly honored to return this historically important document back to Spain – its rightful owner. I commend the dogged efforts of HSI special agents and Department of Justice attorneys who are dedicated to the recovery of stolen cultural artifacts from around the world.”

Today’s repatriation marks the second return of a Columbus letter by ICE, the most recent until now taking place in May 2016.

ICE has returned over 11,000 artifacts to over 30 countries since 2007, including paintings from France, Germany, Poland and Austria, 15th-18th century manuscripts from Italy and Peru, cultural artifacts from China, Cambodia, and two Baatar dinosaur fossils to Mongolia, ancient artifacts including a mummy’s hand to Egypt, royal seals valued at $1,500,000 to the Republic of Korea, and most recently, thousands of ancient artifacts to Iraq.

Learn more about ICE’s cultural property, art and antiquities investigations. Members of the public who have information about suspected stolen cultural property are urged to call the toll-free tip line at 1-866-DHS-2-ICE or to complete the online tip form.

German museum and auctioneer Im Kinsky tussle over looted glass goblet

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/museum-auctioneer-tussle-over-looted-goblet

German museum and auctioneer Im Kinsky tussle over looted glass goblet

Object was returned to consigner not museum from where it was looted at the end of Second World War

CATHERINE HICKLEY – June 6, 2018

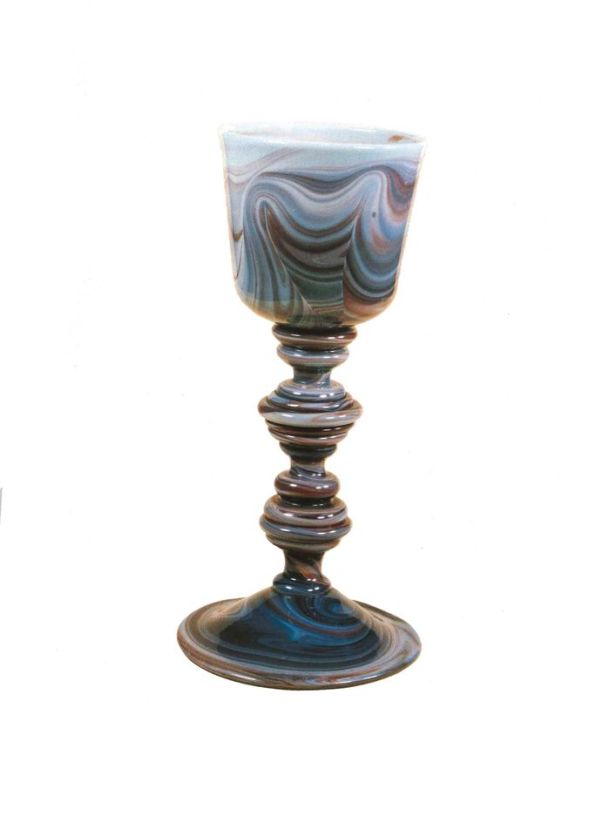

A multicoloured marbled glass goblet dating from around 1800, which was stolen at the end of the Second World War, is the subject of a dispute between the Vienna auction house Im Kinsky and Berlin’s Märkisches Museum.

The museum bought the goblet at auction in 1890 along with eight similar glass objects, all of which were looted in the chaos at the end of the war. Little was known about the goblet’s history until it was offered for sale at the Glasgalerie Michael Kovacek in 1990, according to Im Kinsky’s lawyer Ernst Ploil, on consignment for a German seller. The museum tried to recover the glass at that time, but Kovacek failed to stop the sale.

The goblet surfaced again this year at Im Kinsky in Vienna, where Kovacek and Ploil are managing partners. In the catalogue for the auction on 25 April, the provenance history included the brief description “Museum Berlin”.

At the request of Ulf Bischof, the Berlin lawyer representing the Märkisches Museum, Im Kinsky withdrew the goblet from the auction and returned it to the consignor. The museum then offered to pay a “finder’s reward” of €5,000 to avoid a legal battle but the consignor rejected the offer, saying he had another potential buyer who was offering €48,000.

“Our client is deeply concerned by this behaviour,” Bischof says. “It is unprecedented that an auction house knowingly accepts a stolen museum work on consignment and uses a cryptic ‘Museum Berlin’ provenance for advertising.

“Collectors as well as the museum community should be alerted to such questionable business practice.”

Bischof says the goblet was produced at Zechlinerhütte, a former glass-making centre in Rheinsberg, north of Berlin.

It is not known exactly how it came to be lost in the Second World War, but many Berlin museums stored their collections in bunkers and other bomb-proof locations to protect them from air raids. Some of these stored treasures were plundered by the Red Army; others were looted by ordinary German citizens.

Ploil argues that statutes of limitations would hinder any efforts by the museum to pursue its claim in court and that the previous buyers bought the goblet in good faith, thereby obtaining legal title.

“The fact that the goblet was previously in the museum was known, but no one knew it was stolen,” Ploil says. “Any restitution claim for this has expired.”

Bischof says that the Märkisches Museum still holds legal title. He insists that whoever buys it now cannot claim a good-faith purchase because the seller is aware of its tainted past. Any attempt to sell the goblet without informing the buyer in full of the ownership claim may be liable for fraud, he says.

Bischof also argues that even though the theft itself is time-barred under statutes of limitation, laws against concealing stolen goods are still applicable. He has informed Austrian law enforcers.

Stolen Spencer masterpiece returned to owners

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/stolen-spencer-masterpiece-returned-to-owners

PRESS RELEASE – Jun 3, 2018

Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport and Arts Council England

Stolen Spencer masterpiece returned to owners

A valuable painting by one of England’s greatest 20th-century artists has been returned to its owners five years after it was stolen from a gallery.

Cookham from Englefield by Sir Stanley Spencer was on loan to the Stanley Spencer Gallery in Cookham in 2012 when thieves broke in through a window and removed it.

The owners said they were devastated at the loss of the painting, which was of great sentimental value.

However, they were compensated for the loss of the painting by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport under the Government Indemnity Scheme. The scheme provides UK museums and galleries with an alternative to commercial insurance, which can be costly. It allows organizations to display art and objects that they might not have been able to borrow due to high insurance costs.

Five years after the theft of Cookham from Englefield, police discovered the painting hidden under a bed during a drugs raid on a property in West London.

A 28-year-old man was sentenced at Kingston Crown Court in October after he pleaded guilty to conspiracy to supply class A drugs and acquiring criminal property. He also admitted a charge of handling stolen goods. Last month the owners were finally reunited with their painting

Arts Minister Michael Ellis said:

Spencer is one our most renowned painters and a true great of the 20th century. It is wonderful that this story has had a happy ending and the painting has been returned to its rightful owners.

This has been made possible because of the Government Indemnity Scheme. It exists to protect owners when lending their works to public galleries. Without it there would be fewer world class pieces on display across the country for people to enjoy.

Detective Inspector Brian Hobbs, of the Met’s Organised Crime Command, said:

I am pleased to say that the painting has now been returned to its owners. The seizure of the painting was the result of proactive investigation by the Organised Crime Command, which resulted in a significant custodial sentence for the defendant found in possession of the painting.

Detective Constable Sophie Hayes, of the Met’s Art and Antiques Unit, said:

The Art and Antiques Unit was delighted to assist with the recovery and return of this important painting. The circumstances of its recovery underline the links between cultural heritage crime and wider criminality. The fact that the painting was stolen five years before it was recovered did not hinder a prosecution for handling stolen goods, demonstrating the Met will pursue these matters wherever possible, no matter how much time has elapsed.

Sir Stanley Spencer (1891 – 1959) was an English painter known for his works depicting Biblical scenes of his birth place Cookham. He is one of the most important artists of the 20th century and during the Second World War was commissioned by the War Artists’ Advisory Committee.

It is estimated that the Government Indemnity Scheme saves UK museums and galleries £14 million a year. In the last ten years of the scheme, only 12 claims for damage and loss have been received. This incident is the first one where an item covered by the Scheme has been stolen and successfully returned to its original owners. In line with the rules of the Government Indemnity Scheme for return of the painting, the owners repaid the amount they had received in settlement of the claim minus the cost of repairs and depreciation.

Notes to editors:

- The Government Indemnity Scheme is administered by Arts Council England on behalf of DCMS.

- In the event of loss or damage to an object or work covered by the scheme, the government compensates the owners.

LOST MASTERPIECES – He Stole Priceless Old Masters. His Mom Destroyed Them—And Him

LOST MASTERPIECES – He Stole Priceless Old Masters. His Mom Destroyed Them—And Him

ALLISON MCNEARNEY – Jun 1, 2018

Stéphane Breitwieser stole over $1 billion-worth of art, one of the most prolific art thieves of modern times. He loved what he stole. His mother Mireille, disastrously, did not.

It was a rare, 16th-century bugle that finally took him down.

Stéphane Breitwieser was visiting the Richard Wagner Museum in Switzerland and was captivated by the magnificent brass piece that was one of only three that existed in the world. So he did what came naturally to him after nearly seven years of indulging his love of art—he stole it.

But this time, unlike hundreds of times before, his brazen actions did him in. When he decided to return to the museum two days later to see what else might catch his eye, a security guard recognized him and called the police. Breitwieser’s crime spree had come to an end.

For over six years, Breitwieser, an ordinary Frenchman with an extraordinary love of art, trolled museums and private collections across Europe, helping himself to the pieces that caught his eye. He amassed a private collection of his own, to the tune of 239 pieces of art and priceless artifacts from 172 institutions totaling over a billion dollars. He was one of the most prolific art thieves in modern history.

His crimes against the European art world were bad enough. But Breitwieser committed one other unforgivable sin—he entrusted much of his hoard to his mom.

When the law eventually caught up to him in late 2001, his dear mamanMireille destroyed over 100 pieces of art and precious artifacts that were residing in her home and that were ultimately thought to be worth $30 to $40 million.

It all started when Breitwieser was a young lad in his early twenties. He had embarked on a career as a waiter, working mostly across the border from his hometown of Mulhouse, France, in Switzerland. While that may have been his day job, Breitwieser professed to be a “self-taught art lover.”

In 1994, according to a 2005 article in Forbes, he was visiting the Musée des Amis de Thann in Alsace, France, when he became enraptured by an 18th-century pistol.

It was the lax security around the piece that spurred him to make a move that would eventually define his life. Noticing that the case was unlocked, Breitwieser decided to relieve the museum of their antique firearm.

“The pistol fascinated me. My heart was going 100 miles an hour, I was terrified, but I was driven by passion. I asked myself, ‘What’s holding me back?’” Breitwieser said. “Afterwards, I slept with the pistol beside me—I cleaned the wood, removed the rust; I treated it like a baby I was nursing. But I was still very frightened. Each day for a month I bought the newspaper, but the museum said nothing about the theft—a lot of museums prefer to smother these affairs. Eventually I calmed down.”

In his own memoir and to other journalists, he claimed that his spree began a year later, in 1995, when he and his girlfriend were visiting a castle in Switzerland.

There, he saw an 18th-century painting that wasn’t that valuable, but that reminded him of a Rembrandt.

“I was fascinated by her beauty, by the qualities of the woman in the portrait and by her eyes,” he told The Guardian in 2003. “I thought it was an imitation of Rembrandt.”

So, while his girlfriend played lookout—a role she would embrace for the remainder of his criminal career—he relieved the canvas of its frame, stuffed it under his jacket, and took it home.

He has maintained that his criminal inclination stemmed purely from a passion for the objects that fell victim to his sticky fingers. “I did it because I loved these things, because I simply had to possess them,” he told a writer for Forbes who also noted that he showed “not a shred of remorse.”

But it seems he may have been equally tempted by the lax security that plagues many smaller museums. “There was often no watchman or anything—all you had to do was bend down and pick something up,” he said.

Whether it was the antique pistol or the Rembrandt look-alike who proved his gateway drug, stealing art became an almost instant addiction. Until he was caught in November 2001, the waiter continued to travel around France, Switzerland, and other European countries and filch the treasures that caught his eye.

Particularly early on, these treasures were Old Master paintings. He took Pieter Brueghel’s “Cheat Profiting from His Master,” François Boucher’s “Sleeping Shepherd,” Corneille de Lyon’s “Mary, Queen of Scots,” and Antoine Watteau’s drawing “Two Men.” The most famous Old Master he stole was Lucas Cranach the Elder’s “Sybille, Princess of Cleves.”

But in addition to the Old Master paintings, Breitwieser increasingly helped himself to antique objects and artifacts of value. They ranged from ceramic pieces, vases, jewelry, priceless musical instruments, antique weapons, and much more.

“Looking back on this case, there was a pattern of just one or two objects being taken from different museums. But we thought it was the work of a gang. What happened here was simply unimaginable,” Alexandra Smith, operations manager at the Art Loss Register, told The New York Times.

The art thief wasn’t just exceptional for his audacity—according to experts in the field, serial thieves of fine art are very unusual; he was also unique in what he did with his spoils. Breitwieser wasn’t interested in profiting from his hobby, and he never attempted to sell a single piece. He truly wanted the pieces he took for his own enjoyment.

He stored most of his loot in his bedroom at his mom’s house in Mulhouse, France, and he took the utmost care with each treasure.

He often reframed the canvases before arranging them in his makeshift bedroom gallery in which, according to Anthony M. Amore and Tom Mashberg in Stealing Rembrandts: The Untold Stories of Notorious Art Heists, he “kept the lights dim and the shades drawn to protect the paintings from fading.”

He did everything he could to care for the art. Everything, that is, except pass his “handle with care” mantra on to his mother.

After Breitwieser was arrested, his girlfriend-cum-accomplice informed his mom of what had happened.

Mireille freaked out. While she initially claimed that she had no idea the value of the works and that she destroyed them out of anger toward her son, many of the authorities involved have suspected that she did what she did out of loyalty.

And what she did turned what could have been an intriguing art theft caper into a tragedy.

Mireille got to work destroying all traces of evidence. She shredded 60 Old Master canvases, putting some of the pieces down the garbage disposal and throwing others out in the trash along with the broken frames.

Then, she rounded up 109 of the artifacts, statues, and antiques her son had collected and she unceremoniously dumped them in the Rhône-Rhine Canal. It is thought that she destroyed around two-thirds of Breitwieser’s entire haul.

Though utterly disastrous, her actions were initially effective. Unfortunately, she and her son were not on the same page.

Once in custody, Breitwieser hoped that the evidence of his crime would help get him out of his bind. He quickly confessed all, told the authorities where they could find his loot, and even, according to Guardian reporter Jon Henley, hoped his cooperation might help him win brownie points that would result in his being asked to advise some of the very same institutions he had robbed.

But when the authorities arrived at his mother’s home a week later, all traces of that evidence he had pointed them to were gone. It was only after ancient artifacts began washing up on the banks of the river that they started to suspect the true depth of the crime. It would take them several more months to get Mireille to confess to her role in the crime.

Given the extent of the destruction to cultural artifacts and priceless works of art, the parties involved got off with relatively light punishments.

Mireille served 18 months in prison, Breitwieser’s girlfriend did six months for her role, and the serial art lover-turned-thief served several years in Switzerland before being sentenced to 26 months in jail in France. In 2006, Breitwieser wrote a memoir titled Confessions of an Art Thief.

Perhaps Breitwieser’s punishment was worse than it seemed. After all, the “eccentric kleptomaniac,” as Smith called him, never stopped claiming he acted out of a love for the art. And in the end, that love was what led to their destruction.

While awaiting his sentencing in a jail in France, Breitwieser attempted suicide. Some reports claimed he did so after learning the fate of his precious treasures.

What’s the motive for museum thefts?

https://www.apollo-magazine.com/whats-the-motive-for-museum-thefts/

What’s the motive for museum thefts?

Two recent museum thefts can be taken to illustrate the thinking behind such crimes. One, in Nantes, saw thieves snatch a 16th-century solid gold reliquary containing the preserved heart of a French queen from the Thomas-Dobrée museum. The other, in Bath, involved the theft of Chinese jade and gold from the Museum of East Asian Art.

The Nantes theft was carried out in the night between 13 and 14 April, with the thieves breaking in through a window. Although the loss of the heart of Anne of Brittany, which had only gone back on display on the Tuesday of the preceding week, attracted the majority of attention, the thieves also took a range of gold coins and medals and a gilt sculpture of a Hindu deity – the latter presumably in the mistaken belief that it too was gold. This theft appears to be a prime example of opportunism. The return to display of the reliquary presumably drew the attention of the thieves and they then took the first available opportunity to take it, and other items that appeared valuable to them at the same time. Little planning was presumably carried out if amongst their haul of gold was a gilt sculpture of far lower financial value. The fact that the reliquary was subsequently buried just outside Saint Nazaire (a nearby town), from where it was recovered after police were led to it following two arrests, indicates that it is unlikely that the thieves had thought beyond the initial ‘smash and grab’ element of their crime and had not considered how to dispose of their haul.

In contrast – although superficially similar in that the thieves broke in through a window during the early hours of the morning – the theft from the Museum of East Asian Art in Bath on 17 April appears to have been highly targeted. The pieces taken seem to have been selected based on their quality and cultural significance, rather than simply their material, which ranged from jade to soapstone to zitan wood, or obvious financial value. The thieves made their selection of objects rapidly and fled the scene in under five minutes before the police could arrive, indicating that significant planning must have gone into the robbery. Again in contrast to the Nantes theft, as yet it appears that none of the material stolen has been recovered, nor have any arrests been made.

This is not the first time that a European museum has suffered from what appears to be a targeted theft of Chinese material. Similar thefts have taken place over the last decade in Durham, at the Fitzwilliam in Cambridge, and at the Château de Fontainebleau. This kind of crime appears to be carried out with a specific view to then selling the pieces stolen to the Chinese market where it is relatively easy to find a buyer, and the chances of a piece being identified are far lower than if it were offered to the Western art market.

Sadly, museums are particularly vulnerable to targeted thefts such as this. Their very nature, with publicly listed catalogues of their collections (the full collection of the Museum of East Asian Art is available online), and outreach programs to ensure that people are aware of their existence and holdings, means that for those who are seeking particular types of item and are prepared to secure them through illicit means they are almost a shop window for criminals. It is essential that museums resist the temptation to keep their collections private, but their public nature does mean that it is also essential to factor in security when planning exhibitions, building works, and storage.

Equally, museums remain vulnerable to opportunistic theft of pieces on display such as appears to have been the case in Nantes. It is rare, but criminals see the pieces within museums as valuable, and thus worth stealing if an opportunity to do so arises. As in this case though, they rarely have a plan for how to turn that value into cash, and thus end up hiding the items when it becomes clear that they are not as easy to fence as they might have hoped.

Ultimately, for the general public, historians, and museums themselves, the outcomes of these thefts are often sadly indistinguishable: the loss of items integral to their collections. Tackling museum theft is dependent upon financial resources for security and policing, but for museums, especially those with lower budgets, an increased awareness of the types of items likely to be liable to targeted theft, and of the risks of opportunistic theft prompted by publicity, is well worth keeping in mind.

James Ratcliffe is director of recoveries & general counsel at the Art Loss Register, London.

Man attacks ‘Ivan the Terrible’ painting with a pole in Moscow

https://www.cnn.com/style/article/ivan-the-terrible-painting-attack/index.html

Man attacks ‘Ivan the Terrible’ painting with a pole in Moscow

Drunk on vodka, a man attacked one of Russia’s most famous paintings with a pole, badly damaging the artwork.

The painting, “Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on November 16, 1581,” was created by Ilya Repin, one of Russia’s most famous 19th-century artists, and housed at the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. Painted in 1885, the piece depicts Ivan the Terrible — czar of Russia from 1547 to 1584 — consoling his son after having dealt him a mortal blow in a fit of rage.

The 37-year-old man — one of the last visitors to the museum — entered just before the museum closed, according to a statement by the Tretyakov Gallery. Armed with a pole from one of the painting’s barriers, the man struck the glass case protecting the piece several times.

“The picture is badly damaged. The canvas was broken in three places in the central part of the image on the figure of the prince. The artist’s original frame was badly damaged by falling glass,” the museum said in a statement.

The painting may have been badly damaged, but the face and hands of Ivan and his son were left untouched. Museum employees detained the man before he was able to cause any more damage to the art piece and handed him over to the police, according to the Tretyakov Gallery.

Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs spokeswoman Irina Volk confirmed the incident in a statement, saying “a man had been arrested in connection with the defacing of the painting. He has been charged with damage or destruction of an object of cultural heritage.”

Museum curators and restorers arrived shortly after the incident to evaluate the painting’s damage. With the help of leading Russian specialists, the museum hopes to restore the piece.

State television showed police footage of the unnamed suspect, who said he decided to attack the painting after downing vodka in the gallery’s buffet.

“I wanted to leave, but then dropped into the buffet and drank 100 grams of vodka,” he said. “I don’t drink vodka and became overwhelmed by something.”

Girl, 17, plotted grenade attack on British Museum, court told

Girl, 17, plotted grenade attack on British Museum, court told

Safaa Boular allegedly began to plan terrorist attack after her Isis militant fiance was killed in Syria

A teenage girl plotted to launch a gun and grenade attack on the British Museum after her attempts to become a jihadi bride were thwarted, a court heard.

Safaa Boular was 17 when she allegedly decided to become a “martyr” after her fiance, an Islamic State militant was killed in Syria.

She was so determined to attack London that she enlisted the help of her older sister after she was charged with planning to go to Syria, the Old Bailey heard on Thursday.

Rizlaine Boular, 21, had already admitted planning an attack in Westminster, that was allegedly to involve knives, with the alleged help of their mother, Mina Dich, 43, the jury was told.

Duncan Atkinson QC, prosecuting, told how Safaa Boular’s alleged plotting followed a failed attempt to marry the Isis member Naweed Hussain.

The couple declared their love for each other in August 2016, after three months of chatting on social media, the court heard.

Atkinson told jurors Boular wanted to join Hussain in Syria where they would carry out an attack. He said: “Their plan then was that together they would, as Hussain put it, depart the world holding hands and taking others with them in an act of terrorism.”

The court heard Rizlaine Boular had also tried to go to Syria two years before.

After Safaa Boular’s plan was uncovered, she allegedly switched her attention to Britain, keeping contact with Hussain through the encrypted messaging service Telegram.

The security services deployed specially trained officers to engage in online communication with them, jurors heard.

Atkinson said: “It was clear that Hussain had been planning an act of terrorism with Safaa Boular in which she could engage if she remained in this country. Both Hussain and Safaa Boular talked of a planned ambush involving grenades and/or firearms.”

She also told an officer posing as an Isis militant that all she needed was a “car and a knife to get what I want to achieve”, the court heard.

Atkinson said: “Based on her preparation and discussion, it appears she planned to launch an attack against members of the public selected largely at random in the environs of that cultural jewel and most popular of tourist attractions, the British Museum in central London.”

An attack would have caused at least widespread panic and was intended to cause injury and death, the court was told.

When she learned Hussain had been killed in April 2017, Boular’s determination was strengthened, the court heard. She was allegedly encouraged by her mother and sister to become a “martyr”.

But within days, she was charged with planning to go to Syria and was unable to carry out her “chilling intentions”, Atkinson told the court.

He said: “However, that those intentions were not just chilling but sincere and determined is demonstrated by the fact that she did not abandon them even when she was unable to put them into effect herself. Rather, she sought to encourage her sister Rizlaine to carry the torch forward in her stead.”

Atkinson told jurors that Rizlaine Boular, of Clerkenwell, central London, had admitted preparing acts of terrorism, which was apparently to be a knife attack in Westminster.

Safaa Boular, now 18, who lived at home with her mother in Vauxhall, south-west London, denies two counts of preparing acts of terrorism.

The trial continues.

Common art exhibition rules and why you should obey them

Common art exhibition rules and why you should obey them

Keep your hands off the artworks

Unless it’s an interactive art exhibition where you can touch and feel the artwork, you had better keep your hands off the artist’s work. Several art galleries don’t apply a borderline between the artworks and visitors, but this does not mean visitors can touch the artworks. Moisture and bacteria from your fingers could ruin the artwork.

Leave your selfie stick at home

Major art galleries and exhibitions around the world don’t allow their visitors to bring selfie sticks. While it is tempting to take selfies with famous artworks, refrain from using selfie sticks as it may damage the artworks and disturb other visitors.

No flash

The flash from your camera is strictly banned in art exhibitions. Overexposure of lights may damage artworks as it may change their colors.

Be considerate of others when taking photos

Taking selfies is allowed in museums, however, don’t hog an artwork as a background for your selfie for a long time. Be aware that there are other people who also want to enjoy the artwork. Several museums have even set a time limit for those who want to take a picture with an artwork.

No professional camera allowed

Some art exhibitions ban visitors from taking pictures using professional cameras, especially in painting exhibitions as this puts the artworks at risk of being duplicated.

No food and drinks in the art space

Bringing food and drinks into the exhibition space will disturb others, and will also put the artworks at risk. Have a nice meal before you go to an art exhibition, and enjoy the artworks comfortably afterward.

Take note of age limitations

Some art exhibitions have strict age restrictions, with security and comfort in mind. Be considerate to other visitors by complying with this rule.

Artworks are not only for selfie backgrounds

Art exhibitions are held to educate the public about artworks. Each of the artworks displayed has its own story and meaning that the artist has tried to convey. Try to read the information about the artwork, observe and attempt to understand the correlation between the artwork’s form and its meaning. For those who upload photos of artworks to social media, do not forget to always credit the artists, as a form of appreciation.