Spanish Police Arrest Two in Barcelona on Suspicion of Selling Stolen Art to Finance IS

https://uk.news.yahoo.com/spanish-police-arrest-two-barcelona-115032567.html

Spanish Police Arrest Two in Barcelona on Suspicion of Selling Stolen Art to Finance IS

Police in Barcelona said on March 28 that a network that traded in stolen Libyan artworks to fund groups affiliated with the Islamic State had been dismantled.

Two Spaniards aged 31 were arrested for their alleged involvement in the operation.

According to the Department of National Security, this was the first police operation in the world to take place “against the theft of art in territories besieged by terrorist groups.” Credit: Policia Nacional via Storyful

Belgian Police Discover 84 Pages of Stolen Albert Uderzo Art in Forest

https://www.bleedingcool.com/2018/03/24/stolen-albert-uderzo-art-found-forest/

BLEEDINGCOOL

Belgian Police Discover 84 Pages of Stolen Albert Uderzo Art in Forest

Eighty-four original drawings were found during a search of the town earlier this month. The art was reported stolen last year after being discovered being sold at auction in Belgium as part of what was called ‘The Rackham Collection’. But after the auction, the art — and the sellers — disappeared.

At the time, Uderzo said the pieces were either stolen or lent out in 2012 and not returned. The owner of the auction house, Alain Huberty, while holding an investigation to determine the origin of the art pieces, stated that he knew the seller is honest, and that any statement from Uderzo that the art disappeared in 2012 is false. And the owner reported they had owned them for 30 years, and no police complaint has been filed.

But the gendarmes were on the hunt. And it was the French police who discovered their location and worked with Belgian authorities to organize a raid within 24 hours.

Denis Goeman, a spokesman for the Brussels prosecutor’s office, put the speed down to Getafix’s magic potion.

The stolen drawings are some of Uderzo’s earliest and predate Asterix, from the ’40s to the ’60s, including childhood drawings, he worked on the Captain Marvel Jr character and also Castagnac, a forerunner of Asterix.

The countries have different laws over art ownership, as a result of the theft of Jewish property during the Second World War. In France, owners of art are obliged to disclose how they acquired them, but not in Belgium. Uderzo describes Belgium as being “a little curious country for not having similar legislation,” which would have prevented the pages being put up for sale in the first place.

Asterix pages and covers regularly sell for six or seven figures, and while these artworks are worthless, in total they would be worth many millions.

No one has yet been charged or arrested and the French investigation continues.

A short history of heists

https://www.varsity.co.uk/arts/15032

Varsity

The independent student newspaper for the University of Cambridge

A short history of heists

Olga Kacprzak – March 25, 2018

Olga Kacprzak looks into infamous cases of art theft over the years

1. A noble thief

One of the most notorious art theft cases dates back to 1911 when Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa was stolen by Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian worker hired by the Louvre. Peruggia was hired to install protective glass cases for some of the works in the museum, including the Mona Lisa. Peruggia was later arrested when he tried to sell the painting in Italy. He claimed it was an act of patriotism and his actions were motivated by the desire to return the artwork to its homeland. Hailed a hero in Italy, Perugia, while found guilty, served only a few months in jail.

2. The woman in gold

Many of the recent art theft cases concern heirs who claim restitution of works looted or misappropriated during the Nazi period. In one of such cases, Maria Altmann sought to recover paintings by Gustav Klimt looted from her family by the Nazis in Austria. The paintings she sought to get back included a portrait of her aunt Adele Bloch-Bauer, often called The Woman in Gold. The portrait was taken by the Nazis when Altmann’s family fled their estate during World War II. The eventual heir of the artwork, Maria Altmann, fought a decade-long legal battle with the Austrian government to reclaim it. Finally, in 2006, the Austrian government was ordered to return the artwork to Altmann. The painting is now displayed at the Neue Galerie in New York.

3. No happy endings

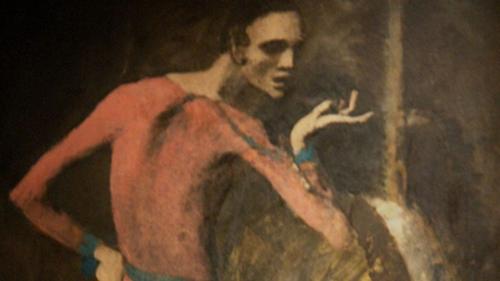

While the courts are generally sympathetic towards the families whose artworks were misappropriated by the Nazis, not all cases end with their success. In a recent ruling, a US court dismissed a lawsuit seeking to order the Metropolitan Museum of Art to return The Actor by Pablo Picasso, which a German Jewish businessman was allegedly forced to sell at a low price to fund his escape from the fascist regime of Benito Mussolini, an ally of Hitler. The heir of the businessman claimed that her family has never lost the title to the artwork because the sale was forced. Still, the court ruled that the claimant could not show that the painting was sold under “duress”, which would justify its return.

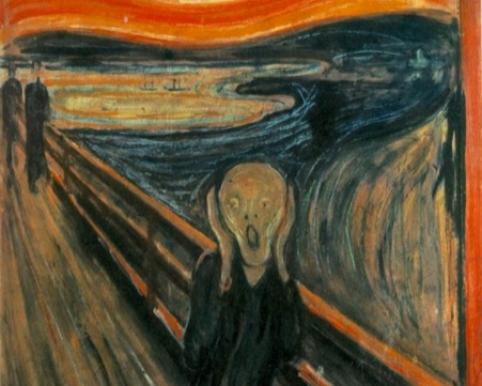

4. A scream piercing the art world

One of the most shocking and emotive art crimes of the last decades is the heist at the Munch Museum in Oslo. In 2004, masked gunmen entered the museum during opening hours and stole the most valuable paintings in its collection – The Scream and Madonna by Edvard Munch. The gunmen threatened security guards before taking the paintings and escaping into an awaiting getaway vehicle. The paintings, recovered after two years, were damaged by the negligent robbers, which raised questions as to the underlying motive behind the heist. According to one theory, the paintings were snatched simply to divert police resources from another crime that happened earlier that year, namely an armed robbery which left a police officer dead.

5. A real-life Ocean’s 12

Last year, a burglar known as Spiderman has been convicted after one of the most audacious art heists to date. Vjeran Tomic gained his nickname by climbing into Parisian apartments and museums to steal valuable objects and artworks. Still, it appeared that the modern day Arsène Lupin did not need any of his skills to steal five paintings worth collectively over €100m from the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris. Tomic broke into the museum with apparent ease, taking advantage of failures in the security system. He initially intended to steal only a Fernand Léger painting titled Still Life with Candlestick but decided to take four more works, including a piece by Picasso and another one by Matisse, as he was able to wander around the museum unnoticed

The Great Feather Heist

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/great-feather-heist-180968408/#4gVe0hbGog655Pcd.03

The Great Feather Heist

Mid-1900s specimens collected in Latin America by Alfred Russel Wallace include parrot wings and marsupial pelts. (Bridgeman / Natural History Museum London)

Of all the eccentrics cataloged by “Monty Python’s Flying Circus,” the most sublimely obsessive may have been Herbert Mental. In a memorable TV sketch, the character zigzags through a scrubby field, furtively tracking something. Presently, he gets down on all fours and, with great stealth, crawls to a small rise on which a birder is prone, binoculars trained. Sneaking up behind him, Mental stretches out a hand, peels back the flap of the man’s knapsack and rummages within. He pulls out a white paper bag, examines the contents and discards it. He pulls out another bag and discards it, too. He reaches in a third time and carefully withdraws two hard-boiled eggs, which he keeps.

The British generally adore and honor eccentrics, the balmier the better. “Anorak” is the colloquialism they use to describe someone with an avid interest in something most people would find either dull (subway timetables) or abstruse (condensed matter physics). The term derives from the hooded raincoats favored by trainspotters, those solitary hobbyists who hang around railway platforms jotting down the serial numbers of passing engines.

Kirk Wallace Johnson’s new book The Feather Thief is a veritable Mental ward of anoraks—explorers, naturalists, gumshoes, dentists, musicians and salmon fly-tyers. Indeed, about two-thirds of the way through The Feather Thief, Johnson turns anorak himself, chasing down stolen 19th-century plumes as relentlessly as Herbert Mental stalked the eggs of birders. Johnson’s chronicle of an unlikely crime by an unlikely crook is a literary police sketch—part natural history yarn, part detective story, part the stuff of tragedy of a specifically English kind.

The anorak who set this mystery in motion was Alfred Russel Wallace, the great English biologist, whose many eccentricities Johnson politely sidesteps. What piqued my curiosity and prompted a recent trip to London was that Wallace, a magnificent Victorian obsessive, embraced spiritualism and opposed vaccinations, colonialism, exotic feathers in women’s hats, and unlike most of his contemporaries, saw native peoples without the gaze of racial superiority. An evolutionary theorist, he was first upstaged, then totally overshadowed, by his more ambitious colleague Charles Darwin.

Beginning in 1854, Wallace spent eight years in the Malay Archipelago (now Malaysia and Indonesia), observing wildlife and paddling up rivers in pursuit of the most sought-after creature of the day: the bird of paradise. Decked out in strange quills and gaudy plumage, the male has developed spectacular displays and elaborate courtship dances whereby he morphs into a twitching, lurching geometric abstraction. Inspired by bird of paradise sightings—and reputedly while in a malarial fever—Wallace formulated his theory of natural selection.

By the time he left Malay, he had depleted the ecosystem of more than 125,000 specimens, mainly beetles, butterflies and birds—including five species from the bird of paradise family. Much of what Wallace had accumulated was sold to museums and private collectors. His field notebooks and thousands of preserved skins are still part of a continuous voyage of discovery. Today the vast majority of Wallace’s birds repose at a branch of the Natural History Museum, London, located 30 miles northwest of the city, in Tring.

The facility also houses the largest zoological collection amassed by one person: Lord Lionel Walter Rothschild (1868-1937), a banking scion said to have almost exhausted his share of the family fortune in an attempt to collect anything that had ever lived. Johnson pointed me to a biography of Rothschild by his niece, Miriam—herself a world authority on fleas. Through her account, I learn that Uncle Walter employed more than 400 professional hunters in the field. Wild animals—kangaroos, dingoes, cassowaries, giant tortoises—roamed on the grounds of the ancestral pile. Convinced that zebras could be tamed like horses, Walter trained several pairs and even rode to Buckingham Palace in a zebra-drawn carriage.

At the museum in Tring, Lord Rothschild’s menagerie was stuffed, mounted and encased in floor-to-ceiling displays in the gallery, along with bears, crocodiles and—somewhat disconcertingly—domestic dogs. The collections house nearly 750,000 birds, representing about 95 percent of all known species. Skins not on show are socked away in metal cabinets—labeled with scientific species names organized in taxonomic order—in storerooms off-limits to the public.

Which brings us back to Johnson’s book. During the summer of 2009, administrators discovered that one of those rooms had been broken into and 299 brightly colored tropical bird skins taken. Most were adult males; drab-looking juveniles and females had been left undisturbed. Among the missing skins were rare and precious quetzals and cotingas, from Central and South America; and bowerbirds, Indian crows and birds of paradise that Alfred Russel Wallace had shipped over from New Guinea.

In an appeal to the news media, Richard Lane, then director of science at the museum, declared that the skins were of immense historical importance. “These birds are extremely scarce,” he said. “They are scarce in collections and even more scarce in the wild. Our utmost priority is working with the police to return these specimens to the national collections so that they can be used by future generations of scientists.”

At the Hertfordshire Constabulary, otherwise known as the Tring Police Station, I was given the lowdown of what happened next. Fifteen months into the investigation, 22-year-old Edwin Rist, an American studying the flute at London’s Royal Academy of Music, was arrested at his apartment and charged with masterminding the heist. Surrounded by zip-lock bags jammed with thousands of iridescent feathers and cardboard boxes that held what remained of the skins, he confessed immediately. Months before the break-in, Rist had visited the museum under false pretenses. Posing as a photographer, he cased the vault. A few months later, he returned one night with a glass-cutter, latex gloves and a large suitcase, and broke into the museum through a window. Once inside, he rifled through cabinet drawers and packed his suitcase with skins. Then he escaped into the darkness.

In court, a Tring constable informed me, Rist admitted that he had harvested feathers off many of the stolen birds and snipped the identifying tags off others, rendering them scientifically useless. He’d sold the gorgeous plumes online to what Johnson calls the “feather underground,” a flock of zealous 21st-century fly-tyers who insist on using the authentic plumes called for in the original 19th-century recipes. While most of the feathers can be obtained legally, there’s an extensive black market for the tufts of species now protected or endangered. Some Victorian flies require more than $2,000 worth, all wound around a single barbed hook. Like Rist, a virtuoso tyer, a surprising percentage of fly-tyers have no idea how to fish and no intention of ever casting their prized lures to a salmon. An even greater irony: salmon can’t tell the difference between a spangled cotinga plume and a cat’s hairball.

In court, in 2011, Rist sometimes acted as if the feather theft was no big deal. “My lawyer said, ‘Let’s face it, the Tring is a dusty old dump,’” Rist told Johnson in the only interview he has granted about the crime. “He was exactly right.” Rist claimed that after about 100 years “all the scientific data that can be extracted from [the skins] has been extracted.”

Which is not remotely true. Robert Prys-Jones, the retired former head of the ornithology collection, confirmed to me that recent research into feathers from the museum’s 150-year-old seabird collection helped document rising heavy-metal pollutant levels in the oceans. Prys-Jones explained that the capacity of skins to provide both new and important information only increases over time. “Tragically, the specimens still missing as a result of the theft are vanishingly unlikely to be in a physical state, or attached to data, that would make them of continuing scientific utility. The futility of the use to which they have probably been put is deeply sad.”

Though Rist pleaded guilty to burglary and money laundering, he never served jail time. To the dismay of museum administrators and the Hertfordshire Constabulary, the feather thief received a suspended sentence—his lawyer argued that the young man’s Asperger’s syndrome was to blame and that the caper had merely been a James Bond fantasy gone wrong. So what became of the tens of thousands of dollars Rist pocketed from the illicit sales? The loot, he told the court, went toward a new flute.

A free man, Rist graduated from music school, moved to Germany, avoided the press and made heavy-metal flute videos. In one posted to YouTube under the nom de plume Edwin Reinhard, he performs Metallica’s thrash-metal opus Master of Puppets. (Sample lyric: “Master of puppets, I’m pulling your strings / Twisting your mind and smashing your dreams.”)

**********

Not long ago I caught up with Johnson, the author, in Los Angeles, where he lives, and together we went to the Moore Lab of Zoology at Occidental College, home to 65,000 specimens, largely birds from Mexico and Latin America. The lab has developed protocols that allow for the extraction and processing of DNA from skins that date to the 1800s. The lab director, John McCormack, considers the specimens—most of which were gathered from 1933 to ’55—a “snapshot in time from before pristine habitats were destroyed for logging and agriculture.”

We entered a private research area lined with cabinets not unlike the ones at Tring. McCormack unlocked the doors and pulled out trays of cotingas and quetzals. “These skins hold answers to questions we have not yet thought to ask,” said McCormack. “Without such specimens, you lose the possibility of those insights.”

He opened a drawer that contained an imperial woodpecker, a treasure of the Sierra Madre of northwest Mexico. McCormack said timber consumption partly accounts for the decline of this flamboyant, two-foot-long woodpecker, the world’s largest. Logging companies viewed them as pests and poisoned the ancient trees they foraged in. Hunting reduced their numbers, too.

Told that he had shot and eaten one of the last remaining imperials, a Mexican truck driver reportedly said it was “un gran pedazo de carne” (“a great piece of meat”). He may have been the final diner. To paraphrase Monty Python’s Dead Parrot sketch: The imperial woodpecker is no more! It is an ex-species! Which might have made a splendid Python sketch if it weren’t so heartbreaking.

Lunar module replica theft still under investigation

http://www.limaohio.com/news/291628/lunar-module-replica-theft-still-under-investigation

Lunar module replica theft still under investigation

WAPAKONETA — In July a solid gold replica of the 1969 Lunar Excursion Module was stolen from the Neil Armstrong Air and Space Museum.

The replica is 5 inches high and around 4.5 inches square and was presented to Neil Armstrong in Paris after his walk on the moon in 1969. There are only three in existence.

Wapakoneta Police Department Detective James Cox said the evidence gathered by the department has been sent to the FBI at Quantico for investigation.

A Theoretical Explanation for the Increase in School Shootings

IN PUBLIC SAFETY

Relevant insights by the experts from American Military University

A Theoretical Explanation for the Increase in School Shootings

By Dr. Michael Pittaro, Faculty Member, Criminal Justice at American Military University

On February 14, Nikolas Cruz, a former student of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, walked onto school grounds and proceeded to randomly gun down students and teachers in one of the deadliest mass shootings in modern U.S. history. Sadly, this story is a familiar one. It has once again ignited a series of national debates, particularly in reference to gun control and mental illness, and rightfully so. Why has there been such a surge in mass school shootings since Columbine in 1999?

There is no single answer to the cause of mass school shootings, but it goes much deeper and further than issues of gun control and mental illness. As a criminologist, I have several theoretical explanations that may shed some light on the topic by focusing on the shooters themselves.

Ever since the mass school shooting at Columbine High School, we can safely surmise that the typical American school shooter is likely to be a Caucasian adolescent male from a middle-class community who attends or attended a suburban high school. Further, the shooter is likely to be a loner, an outcast, and is described by teachers and peers as being socially awkward with a limited number of friends.

Reports also indicate that the majority of school shooters were victims of bullying. Bullying continues to be a pervasive social problem among adolescents and includes both verbal and physical provocation in schools, as well as cyberbullying. Many of the shooters were ridiculed, belittled, demeaned, or even ostracized to the point where it might be assumed revenge or retaliation became a strong motivating force for their actions.

Based on this information, Hirschi’s (1969) Social Control Theory can be used as a reliable and valid psychosocial explanation for school shootings, specifically in understanding the risk factors associated with someone who might resort to such violence.

Applying Social Control Theory to School Shootings

Unlike most criminological theories that explain why people engage in mass shootings and other crimes, Hirschi’s theory explains why people obey rules and remain law-abiding. Social control theories primarily focus on how external environmental and institutional factors influence how we conform to society’s rules and expectations.

Hirschi’s theory consists of four main “social bonds”. When one or more of the following social bonds are weakened, or severed altogether, individuals are more susceptible to crime and deviance.

Attachment

Attachment is expressed as compassion and empathy toward friends, family, coworkers, and even acquaintances like classmates. School shooters lack attachment. They harbor and internalize anger, frustration, and disappointment that can stem from being bullied by their peers, whether real or perceived. These antagonistic emotions grow in the days, weeks, or months leading up to the attack. While some school shooters have targeted specific people, many of them, like Cruz, have fired indiscriminately. The random direction of these shooters’ aim suggests that they have no regard for human life and have rationalized their actions. This is very similar to the cognitive restructuring process that terrorists use to justify the killing of innocent lives.

Commitment

Commitment pertains to the time and energy an individual spends pursuing a specific social goal or activity, such as obtaining a college degree or pursuing a particular position within their desired profession. Most people know that engaging in crime will likely jeopardize their career ambitions and educational goals; therefore, they conform to society’s norms and expectations. However, many school shooters adopt a mindset where they do not foresee a future beyond a shooting event. That is why many of them display a kill or be-killed attitude and are willing to take their own life by suicide or suicide by cop.

Involvement

Individuals who are engrossed in conventional and fulfilling social activities often do not have the time or interest in engaging in unlawful activities. One of the main reasons parents want their children involved in athletics, extra- curricular activities, or any other socially appropriate activity is that it keeps them out of trouble and gives them a sense of belonging to a team, club, or social organization. Individuals who commit school shootings are often described as loners or outcasts, meaning they do not feel like a meaningful part of any group or community.

Belief

The fourth and final bond is when an individual believes in the social rules, expectations, and laws of society as taught to them by parents, family members, and friends as well as educational and religious institutions. The stronger one’s moral beliefs in the social norms, the less likely they are to participate in delinquent or criminal activities. Criminal offenders either disregard society’s shared beliefs or rationalize their own deviant behavior. For example, the belief that killing is wrong is reinforced by parents, education and religion; however, a shooter will disregard what he/she has been taught or rationalize their behavior so they can go through with the mass shooting.

Weak Social Bonds Lead to School Shootings

In order to fully understand and appreciate the paradigm and applicability of Hirschi’s theory, it is important to recognize the historical context from which he wrote Causes of Delinquency (1969). In the 1960s, Hirschi observed a loss of social control over individuals and an accompanying rise in crime, particularly among adolescents. Social institutions such as organized religion, the family, educational institutions, and political institutions were not as prominent in the life of adolescents. As a result, these individuals started to challenge conventional social norms and expectations. Hirschi blamed this on the breakdown of the aforementioned social institutions, particularly the breakdown of the family due to increasing rates of divorce and single-parent households.

Fast forward to present day and this shift in family structure has continued. According to a study by the Pew Research Center, 34 percent of children today are living with an unmarried parent—up from just 9 percent in 1960, and 19 percent in 1980. In most cases, these unmarried parents are single. I feel strongly that individuals who carry out school shootings can lack both resiliency and coping skills due to the breakdown of family structures, as well as reduced value placed on religious and educational institutions. These social institutions are important for molding and shaping individuals and instilling compassion, empathy, and respect for the law and those in authoritative positions.

More importantly, family members, friends, religious leaders, and teachers provide guidance to young people about how to adapt to—and cope with—rejection, disappointment, and frustration. Learning how to be resilient is important for adolescents. The American Psychological Association defines resilience as the process of adapting in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, and other significant sources of stress and how we “learn” to “bounce back” from difficult experiences.

Being resilient does not suggest that an individual does not experience challenges or distress. Rather, it emphasizes how one processes thoughts, behaviors, and actions when confronted with stress. One of the primary ways to build resilience is having a support system of family and friends. This support system is built on compassion and trust, and it provides individuals with unconditional encouragement and reassurance. People need to have a strong foundation of positive self-image and self-confidence to overcome low and challenging moments. While there are many factors that lead to school shootings, all children need to be taught how to manage stress in a healthy way to control their negative impulsive behaviors that often lead to self-destructive outcomes.

Ten Strategies to Build Resilience

The American Psychological Association outlined 10 strategies to build resilience:

- Make connections. Individuals need to build positive relationships with family members, friends and others whom can provide support. Being active in civic groups, faith-based organizations, or other local groups provides social support. It can also be beneficial to help others in their times of need.

- Avoid seeing crises as insurmountable. Highly stressful events happen to everyone, but what counts is how one interprets and responds to them. Try looking beyond the present to how future circumstances may be better. Note any subtle ways in which you might already feel somewhat better as you deal with difficult situations. These are your coping mechanisms and can be consciously applied when you face future challenges.

- Accept that change is a part of living. As you get older, certain goals may no longer be attainable as a result of adverse situations. When you accept that some circumstances cannot be changed, it allows you to focus on other circumstances that you can influence.

- Move toward your goals. Develop some realistic goals. Do something regularly — even if it seems like a small accomplishment — that enables you to move toward those goals. Instead of focusing on tasks that seem unachievable, ask yourself, “What’s one thing I know I can accomplish today that helps me move in the direction I want to go?”

- Take decisive actions. Rather than detach completely from problems and stresses or wish they would just go away, take decisive actions to improve the situation as best you can. Avoidance is not the answer.

- Look for opportunities for self-discovery. People often learn something about themselves and grow in some respect as a result of struggling with loss, rejection, or disappointment. Many people who have experienced tragedies and hardship report later they have stronger relationships, a greater sense of strength even while feeling vulnerable, an increased sense of self-worth, a more developed spirituality, and a heightened appreciation for life. As you’re going through a hardship, remember that there may be benefits in the long run.

- Nurture a positive view of yourself. Have confidence in your ability to solve problems and trust in your instincts. Believing in yourself in a positive way helps build your overall resilience.

- Keep things in perspective. Even when facing very painful events, try to consider the stressful situation in a broader context and keep a long-term perspective. Avoid blowing the event out of proportion.

- Maintain a hopeful outlook. An optimistic outlook enables you to expect that good things will happen in your life. Try visualizing what you want, rather than worrying about what you fear.

- Take care of yourself. Pay attention to your own needs and feelings. Engage in activities that you enjoy and find relaxing. Exercise regularly. Taking care of yourself to keep your mind and body primed to deal with situations that require resilience.

Teaching children and adolescents how to apply these strategies can help them build their resiliency so that when stressful situations happen—which they inevitably will—they have the ability to get through it in the most positive and beneficial way possible. The more equipped people are to cope with stress and adversity, the less chance they will turn to dangerous and impulsive actions, including school shootings.

About the Author: Dr. Michael Pittaro is an Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice with American Military University and an Adjunct Professor at East Stroudsburg University. Dr. Pittaro is a criminal justice veteran, highly experienced in working with criminal offenders in a variety of institutional and non-institutional settings. Before pursuing a career in higher education, Dr. Pittaro worked in corrections administration; has served as the Executive Director of an outpatient drug and alcohol facility and as Executive Director of a drug and alcohol prevention agency. Dr. Pittaro has been teaching at the university level (online and on-campus) for the past 15 years while also serving internationally as an author, editor, presenter, and subject matter expert. Dr. Pittaro holds a BS in Criminal Justice; an MPA in Public Administration; and a Ph.D. in criminal justice.

About the Author: Dr. Michael Pittaro is an Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice with American Military University and an Adjunct Professor at East Stroudsburg University. Dr. Pittaro is a criminal justice veteran, highly experienced in working with criminal offenders in a variety of institutional and non-institutional settings. Before pursuing a career in higher education, Dr. Pittaro worked in corrections administration; has served as the Executive Director of an outpatient drug and alcohol facility and as Executive Director of a drug and alcohol prevention agency. Dr. Pittaro has been teaching at the university level (online and on-campus) for the past 15 years while also serving internationally as an author, editor, presenter, and subject matter expert. Dr. Pittaro holds a BS in Criminal Justice; an MPA in Public Administration; and a Ph.D. in criminal justice.

Belgian police examine claims Russian art show was full of fakes

The Guardian

Belgian police examine claims Russian art show was full of fakes

Homes raided after Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent cancel an exhibition of avant-garde works.

Daniel Boffey in Brussels –

Homes across Belgium have been raided by police investigating allegations that counterfeit Russian avant garde works were exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent.

The display of 26 pieces, loaned by the Russian businessman Igor Toporovski, was terminated by the gallery in January after experts claimed it was full of fakes. The museum’s director, Catherine de Zegher, was suspended from her post earlier this month.

Experts claim Europe has become awash with counterfeit Russian works in recent years.

On Friday, Wiesbaden regional court in the western German state of Hesse sentenced two men to three years and 32 months in prison respectively for having knowingly sold forged pictures that had been presented as works by artists including El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich and Alexander Rodchenko.

The pair were ordered to pay back about €1m (£875,000) they had made through the sale of the pictures.

Ghent’s public prosecutor’s office and federal police in east Flanders carried out their searches on Monday after a formal civil complaint from a collective of four art dealers from London and New York, and a descendant of an artist whose work is said to have been counterfeited.

The prosecutor’s office declined to comment on the targets of its investigation.

Geert Lenssens, a lawyer representing the complainants, said: “They are suffering damage now that the art market, of which they are a part, and the museum world, with whom they work closely, are being damaged.”

Detectives sealed computers, requested documents and interviewed De Zegher, according to the Belgian newspaper De Standaard.

It is believed forgers have focused on Russian avant garde works due to a lack of experts in the genre.

The wave of modern art flourished in the early 20th century, after which socialist realism was decreed the sole sanctioned mode in the Soviet Union, and archives were often destroyed.

The collection under investigation, entitled Russian Modernism 1910–30, was on display for more than three months before being removed on 29 January.

An open letter signed by 10 experts also questioned the validity of the works purportedly by artists including Malevich, Rodchenko, Wassily Kandinsky and Vladimir Tatlin.

De Zegher told the city’s cultural committee on 5 March that her 35 years of curatorial experience qualified her to recognise fakes.

She claimed to have consulted two foreign experts, Noemi Smolik and Magdalena Dabrowski, on the authenticity of the collection. However, Smolik and Dabrowski refuted the claim in the Flemish press days later.

Eline Tritsmans, a lawyer acting for De Zegher, declined to comment “in the interests of the judicial investigation”.

Annelies Storms, the alderman for culture in Ghent, said: “We are always confronted with new issues. It is easy to say afterwards what someone has to do.”

Museums: A Whole New World for Visually Impaired People

http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/3761/3276

Accessing museums has been difficult for people who are blind or partially sighted, often due to objects being placed in glass cases creating a barrier to access. Many museums around the world provide some accessibility but what happens when a museum looks at the issue in its entirety and sees blind and partially sighted visitors as important as everyone else.

The Victoria & Albert Museum in London has tried to take an holistic approach to access, by looking at what prevents blind and partially sighted visitors visit a museum and how it can improve access for such an audience.

Taking a focused approach to consider not only the objects but implementing a museum wide strategy is required to provide inclusive access for all visitors. The museum considers how it can improve the visitor experience by removing the physical barriers, staff training, providing touch objects and tactile books, as well as looking to the future to see how technology can play a part in improving access.

Employing people with a disability has also assisted the V&A in its journey to becoming more accessible by employing a blind person as its first Disability and Access Officer, a unique opportunity to change from within.

Introduction

The Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) in London is the world’s largest museum of art and design. First opened in 1857, the museum is housed in seven Grade 1 Listed buildings, which combine to form one large building and seven miles of gallery space. A listed building, in the United Kingdom, is a building that has been placed on the Statutory List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest, similar to the National Register of Historic Places in the United States. However, this gives us the opportunity to show how an historic building which was not designed with disabled people in mind can be made into an accessible environment for all users in the twenty first century.

The V&A is part of a family of museums consisting of The V&A in South Kensington and the V&A Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green. It also operates an accessible archive and store at Blythe House in West London (jointly run with the British Museum and the Science Museum).

The purpose of the Museum is to enable everyone to enjoy its world class collections and to explore the cultures that created them: to inspire those who shape contemporary design.

Over the past ten years, the museum has been pro-active in developing inclusive and accessible services and premises for its visitors, including those with sight problems. The V&A’s aim is for disabled people to come in off the street, just as any visitor would, to enjoy the collection. Historically this approach has not been the norm for museums as many would not be either physically or intellectually accessible. This is why in the V&A’s FuturePlan, a redevelopment of the South Kensington and Museum of Childhood sites, access for disabled people is a priority.

FuturePlan

FuturePlan is an ambitious programme dedicated to restoring and enhancing the V&A’s original 19th century architecture, opening up previously hidden areas to the public and improving visitor facilities. Over the past ten years 70% of the Museum’s public space has been transformed through FuturePlan phase 1. Following the completion of the British Galleries in 2001 more than forty FuturePlan projects have been completed, transforming accessibility throughout the museum.

The picture below shows the V&A entrance completed in 2001, where a ramp now gives access to wheelchair users to the main entrance. This is great for wheelchair users, who can now gain access to the entrance, but what happens when you get inside? And what about other visitors with disabilities? What facilities are there for visually impaired visitors in particular? This article will show how the V&A has taken a long term approach on accessibility through FuturePlan and considered visually impaired people when implementing services and policies.

Cromwell Road Entrance, V&A Museum

Organisational Strategy

Organisations need to consider that accessibility is not only physical adaptations to buildings, it is about the management and services which also aid access. By creating a strategy that pulls together all elements of disability into one document focusing on the moral, legal and business case and how that can impact on day-to-day activities for both staff and visitors.

The V&A began this process in 2002 when it employed me as the museum’s first Disability and Access Officer. I was also the first blind employee of the V&A. This was a new area of work, as my previous work experience was providing a consultancy service to the RNIB (Royal National Institute for Blind People) and several property service companies.

As a Consultant for RNIB, I worked to develop improved access to sporting and leisure venues, undertaking access audits and training staff and sports commentators, so working in a museum was a step into the unknown. However, service provision in a museum is the same as it is for sporting venues or other customer facing organisations regardless of the visitors needs e.g. asking a visitor/customer if you can assist works for a museum as well as a retailer. For example, in 1998, I was refused into a cinema as I was told my Guide Dog was “a fire hazard”. The Operations Manager thought he knew what was best for me without asking, surprising as we had never met before. If the Operations Manager had asked how I could be assisted, it would have saved his organisation thousands of pounds in legal fees and compensation as this was the first successful Guide Dog case under the Disability Discrimination Act in the UK, which has set a precedent for all service providers.

I carried out an access audit of the museum to understand the levels of provision for disabled visitors including visually impaired people. The audit looked at the levels of service provision for visitors, and how FuturePlan can achieve accessibility.

The Disability Action Plan published in 2004 highlighted the positives and set out a three-year plan of action for those areas that required attention.

The Disability Action Plan was partly driven by the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) which came into law in 1995, which places a duty on service providers to make ‘Reasonable Adjustments’, remove any physical barriers to accessing the building and also remove attitudinal barriers to allow disabled people to access services. The DDA was based upon the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), however it did not provide the legal rights which came with the ADA. The DDA has now been incorporated into the Equality Act which came into law in 2010.

The Audience

Why is it necessary to provide access to museum collections for visually impaired people? At the V&A, which is partly government-funded, visually impaired visitors are as entitled to gain access to the collection as any other tax payer. As stated above, the DDA places a legal duty on the museum to make ‘Reasonable Adjustments’ to services and collections. If you have always enjoyed art and design, why should you stop once your sight fails?

It is estimated by the Royal National Institute for Blind People (RNIB) that there are about two million people in the UK who are registered blind or partially sighted (Visually Impaired). This means, that for every thirty people within the UK, one will have a sight impairment which substantially affects their day-to-day activities. As the majority of Visually Impaired people are 50 years or older, it is important that adjustments which are made today will also benefit people for the future.

Gallery Interpretation

Visually Impaired visitors are faced with particular issues when visiting the V&A because so much of what is presented in the galleries is visual. The first FuturePlan project to be completed, giving improved access for visually impaired people, was the British Gallery where an Access Consultant was employed and had input into both the interpretation and physical access of the gallery.

The Gallery Interpretation policy developed out of FuturePlan, considers interpretation to be “the bridge between the Museum’s objects and expertise and our visitors’ curiosity and knowledge”. The policy goes beyond labels and panels to include new media that invite touch, action, analysis and reflection. This is a move away from the traditional where museums have hidden objects in glass cases, inaccessible to many people — especially those who cannot see.

The objective of the Gallery Interpretation Policy is that accessible interpretation elements will create a minimum standard for interpretative provision. Three key questions were asked during consultation with Visually Impaired visitors:

- Is the provision clearly marked and easy to use?

- Does the provision significantly aid understanding of subject matter?

- Does the provision encourage further exploration of the V&A from the user?

Touch Objects and Braille

One of the major changes in FuturePlan was to incorporate touch objects into galleries. The Interpretation Strategy has made touch objects the norm in the V&A, allowing all visitors to interact with the objects. Museums used to invite visually impaired visitors in to touch objects after the museum had closed. Doing this when the museum was open would have encouraged able-bodied visitors to touch these objects too. Now, permanently-displayed objects can be investigated and appreciated by all visitors, not just those with a visual impairment.

There has been much debate in the museum sector as to whether original or replica objects should be used as touch objects. The V&A uses both originals and replicas in galleries as it is not always possible to show an original object due to security reasons or its requiring a high level of conservation. Below, is a photo of a Ming vase, in the T. T. Tsui Gallery, which is permanently on display. It is an original made in 1550. The vase is a touch object, giving all visitors, including Visually Impaired people, an opportunity to interpret such a precious object. Located next to the vase is Braille information giving further accessibility. However, due to the height and positioning of the Braille, the object and the accompanying Braille aren’t as user friendly as they should be.

Ming Vase, T.T. Tsui Gallery

By assessing the accessibility in the British Gallery and other gallery projects, the museum learnt much about how touch objects and Braille information should be designed into a display. Initial consultation on touch objects and how they might be displayed was undertaken with visitors with varying success. The museum ran Focus Groups to assess the requirements of visually impaired visitors, researching the preferred height of the objects, the use of Braille and also the type of objects which would be of interest. Some objects were chosen purely because they looked tactile. For instance, blocks of different woods were offered as touch objects so visitors could feel different grains. However, to help conserve the wood, the museum treated it, so preventing the visitor from interpreting the object. This set of touch objects had very little learning before treatment and became completely irrelevant afterwards.

Further learning from the gallery development was the use of interpretive provision aimed at making information more accessible. In the British Gallery, tactile line drawings were installed so visually impaired visitors could understand images such as The Crystal Palace (a building which housed the Great Exhibition in 1851). Raised lines outlined the edge of the structure and significant detail within, with further raised lines leading from the outer part of the panel to letters of the alphabet, indicating important areas of the building. The lines leading from the alphabet directed the user to Braille information. However, the amount of raised lines put into the images made it impossible to follow, thus rendering the activity pointless.

The importance of selecting any object is that it fits in with the story of the gallery and conveys what the Curator wishes it to say. An object should not be chosen because it looks good to touch; it must have qualities which help the visitor to understand the object in relation to the collection and the technique by which it is made. For example, the Ming vase shown above was selected due to it being from a significant period in Chinese history and not just a beautiful object to be touched.

Suitably designing a touch object in a gallery is more than just putting it on a ledge and fixing a Braille panel next to it. For each object for instance, consideration needs to be taken on how high or low it will be positioned since children and adults will all want to touch.

Putting a Braille panel next to an object seems an easy task, however at times you could think you are designing a new rocket system for NASA. Following research undertaken with Visually Impaired visitors, it was found that Braille panels next to objects should be laid flat as this allows visitors of all heights to read comfortably. Occasionally, panels have also been designed to pull out from under the object where space has been a factor.

By assessing the visitor’s interaction with objects and Braille, the following dimensions were found to be usable for a wide range of visitors:

Object height — 30″ from the floor. The base of many objects should be at the specified height to prevent tall people from having to bend forward. However, if you display large objects e.g. motor vehicles, consideration must be taken regarding which part of the vehicle is significant enough to be touched.

Braille information — 30″, flat to a table top or as a pull out panel. It is important that the panels are located next to the object and are not located in any circulation routes which may prevent the label being used.

The inconsistent approach to Braille in V&A galleries could often be difficult for users to find and both Grade 1 and Grade 2 Braille were used. Grade 1 Braille provides information in alphabetical form, being the first level learnt when using Braille. Grade 2, our preferred choice contracts words e.g. the word “The” becomes one symbol and not the three alphabetical characters.

Guidance on how to produce the panels and the specification of Grade 2 Braille, and more importantly the management of the process were outlined. Another failure of the British Gallery was that Braille panels were installed at the wrong object and the manufacturer did not label the panels in print. Also the museum did not have a Braille reader on site during installation. Therefore, written guidance on how this process should be achieved was produced.

The following requirements cover production of Braille and management of the installation process:

- All Braille text should be produced in Grade Two Braille. The Braille should conform to British Braille guidelines and only use Braille symbols such as: punctuation, number signs or letter signs.

- As a general principle the Braille panel should contain the same text as the print label. Occasionally there may be a need for slightly different information in the Braille panel but this should be the exception.

- Braille panels should be located either: flat on a surface with the touch object or as a pull out panel. The Braille panels should never be located flat on walls as this is difficult to read by Braille readers as a person’s height may prevent them from comfortably reading the text.

- The specified height from floor level of the panel should be no less than 30″. This allows children and wheelchair users who are Braille readers to have access to the information.

- All Braille panels must be checked by a Braille reader before any manufacturing takes place. On receipt of the Braille panels, proof reading by a Braille reader must be carried out before installation.

- The Braille reader should also be available during installation and on hand to check that the panels are being installed at the correct object.

Audios and Audio Description

The V&A is moving away from the use of Braille for touch objects in galleries as there is a limited audience who read Braille. With the limitations on funding and the will to provide access to a wider audience the museum wishes to provide greater accessibility through new technology. Audio descriptions of objects are being written and recorded to assist visually impaired visitors to listen to descriptions downloaded via their own smart phones.

Over the past several years, the V&A has been assessing the accessibility of multimedia guides in many organisations which provide information to all visitors in their chosen format. The aim would be for the museum to provide a system which is both user friendly to all visitors and accessible to those who are not as technically minded or have been excluded by new technology.

I visited three museums whilst in Boston in the United States in 2011 and assessed two multi medias, one at the Hall of Patriots Place an American Football Museum who use an Infrared system and the Museum of Fine Art in Boston who use I Pods.

Both systems had benefits and drawbacks, meaning that not one system would satisfy all user needs including those who are Visually Impaired. Benefits such as language selection and audio features made the systems more accessible, where usability in selecting menus and options on touch screens may be a barrier to independent usage. Therefore, in the short term the V&A will provide audio descriptions in an MP3 format which is downloadable from the museum’s web site.

In 2006, the first audio descriptions accompanied videos in the Jameel Gallery of Islamic Art. These descriptions have proved beneficial for all as the Describer highlights significant images within the video which even many sighted visitors had not noticed such as certain colours or inscriptions. Further audio descriptions have been developed for the Furniture Gallery which opened in December 2012 and the Europe Gallery which opens in 2014. The new audio descriptions will be available both in the galleries and via the museum’s web site.

A self-guided audio trail had also been planned to take Visually Impaired visitors around the museum, locating ten touch objects. Due to the complexity of the building and the large walking distances, only the audio description of the objects has been produced, and not the directional information as first planned.

Complex buildings such as the V&A with eighteen split levels make it impossible for visitors to follow directions, especially those with a visual impairment. Audio guides in some museums give directions from object to object by using stride length and then visual clues. As people’s strides differ and not all visually impaired people are prepared to stride out in unfamiliar places, this directive becomes non-effective. Only when internal guidance systems similar to external GPS are available will visually impaired people be able to self guide around large museums like the V&A.

All of the ten audios can be downloaded from the museum’s website in an MP3 format, making it accessible to all smart phones and MP3 compatible phones. However, visitors who do not use smart phones are not forgotten as the museum will provide the audios on a device which can be picked up on arrival at the museum.

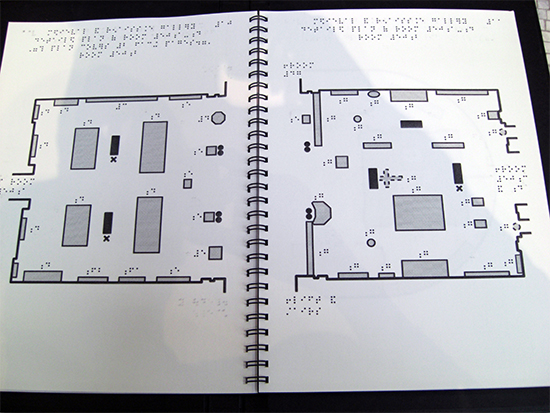

Tactile Books

Being able to access photographs and paintings can be difficult for Visually Impaired people. Audio Description as outlined above can assist, however using a tactile image can add to the description given enabling the visitor to further interpret the work. The V&A has developed its provision since first making line drawings available to visitors in the late 1990s, interpreting images for the Photography Gallery.

Books developed for the Paintings Gallery took on both the tactile image form and techniques we use today. However, not all Visually Impaired people have been taught to touch which can make reading tactile images difficult, so on occasion it is necessary to remove less important elements enabling the user to focus on key images of the work.

To try and develop this form of interpretation further, the V&A has worked with the Royal National Institute for Blind People to make tactile images more accessible. The tactile books have: Braille information of gallery panels; gallery plans so the visitor can orientate themselves in the gallery; and descriptions of the tactile images as well as the tactile image itself. Where necessary, the images have been simplified to highlight the key elements of a picture.

Tactile Book With Braille Description

To help the V&A and RNIB further get it right, a focus group was run to develop resources for the Medieval and Renaissance Gallery, the final FuturePlan project. The group, all Braille readers, evaluated the tactile images and their accompanying descriptions with the following outcome for producing tactile image books:

- The images must be interesting and informative.

- Textures and lines must be distinguishable.

- Braille labels on the images in full where at all possible.

- Have a key on the image page when abbreviations have to be used due to space limitations.

- Keep titles simple.

- Do not mention things that are not shown unless relevant to the image.

It is not enough to just have the tactile images – having only half of the information does not give equal access. Description of the images was written to help the visitor navigate around the image. From the Focus Group, the following directions helped when looking to provide images and text:

- The descriptions must explain the image so the visitor understands. Reading and understanding the descriptions takes quite a lot of time so the descriptions need to be written as concisely as possible.

- Ensure that the important details are given first e.g. having to turn the page sideways to read the image.

- Important to have the details about size date etc. at the beginning in order to start the process of understanding.

- Use vocabulary which is suitable for a wide audience.

- Do not assumed knowledge, on occasions further explanation may be required.

Accessible Talks and Events

The Learning Department has developed further interpretive provision by programming talks for disabled people; the V&A is one of the first museums in the world to have done so. The aim of the programme is to encourage disabled visitors to the museum by offering events which cater for their specific needs. The programme focuses on both the permanent collection of the museum as well as special exhibitions.

The V&A first started providing talks and touch tours for Visually Impaired people in 1985 after receiving requests from societies for the blind. The programme soon developed into the programme we have today, where one touch tour or handling session takes place per month or on request. Monthly talks for visually impaired people take place in galleries, led by Curators and V&A Guides complementing the touch objects permanently displayed. Whenever a new gallery opens a programme of events is planned to show visitors the newly displayed objects.

V&A Touch Tour

It is not always possible for visitors to touch objects in an exhibition due to loan agreements with the owners. Therefore, Curators will give a talk and handling session in a seminar room which focus on objects from the exhibition. Although this is not the inclusive experience we would like to offer, touching objects before entering the exhibition allows the visitor a better understanding of the display when described to them.

Planning a touch tour is just like planning any other talk:

- You select your subject and the date of the talk.

- Book a speaker, Curator or V&A Guide.

- Work with the Curator/speaker to select suitable objects which can be touched.

- Arrange for volunteer guides to assist the visitors during the talk.

When leading a touch tour or handling session, the V&A directs the Curator/speaker to consider the following:

- When in a public gallery and walking is involved, then around seven or eight objects to talk about will be sufficient. If it is held in a room as a handling session, eight to ten objects can be used.

- Where possible, allow the visitor to touch objects with their bare hands. Be guided by the Curator who will specify if gloves are to be worn.

- The visitor will need time to examine the objects and there will be long pauses and the need for individual explanations. Always take the pace from the visitor, even if the visitor examines the object before you start your description.

- Focus your description on what is being touched at any time, and offer to guide the hand, when appropriate.

- When objects cannot be touched, it may be useful to use materials or objects which relate to the work being described. Any additional objects or materials, which are to aid a touch tour, should be relevant and not take the visitors mind away from the original piece.

- Only end the session when the visitor is satisfied that they have gained the information they wish to take from each piece.

Behind The Scene Talks

Much work goes on behind the scenes in the museum, from conserving objects to dressing galleries. So visitors can learn about the work undertaken by staff who do not have a customer facing role, behind the scene tours are organised. The talks allow Visually Impaired visitors to touch objects which are in the process of being conserved before going into galleries or exhibitions. For example, visitors to the Stained Glass conservation department watched the making of a stained glass replica that is now permanently displayed in a gallery. Also curators from the Fashion department have demonstrated to visitors how they dressed mannequins for the Ballgowns: British Glamour since 1950 exhibition.

Audio Described Events

Audio Description is often used for television programmes, films and theatre, however the same techniques can be used in describing museum objects or live performances. For example, audio description has enhanced performances in Fashion in Motion, the catwalk fashion show at the V&A starting in November 2004, and also the Chinese New Year celebration.

As both events are live, the Audio Describer is positioned away from the performance but within visual range. Having watched the rehearsals, the describer gets an understanding of the running order allowing them to have prepared information of the performance to hand. The narrator describes information a visually impaired person might not be able to see so they can interpret the subject in a more accessible way. The visitors receive the commentary via radio receivers enabling them to sit anywhere within the auditorium.

The audio described events complement the described talks (verbal description) that happen when objects cannot be touched. To aid speakers to deliver more descriptive talks, including a touch tour to visually impaired people, the museum has developed guidance:

- Each session should last an hour and a half to two hours maximum.

- Take your time – Speak clearly and do not try to overload too much information into a session. Pay close attention to the speed at which you speak, and pace yourself.

- Ask questions to the visitor – this will allow the description to flow and meet the needs of the visitor.

- Do not be afraid to use words such as: sight or see. Use everyday words and terms when describing an object.

- Many blind people who have lost their sight have a visual memory of colours, which will help to build up a picture of the object in their mind.

- The use of size can be beneficial because everyone can relate to it. Using examples of size, from everyday experiences and objects will enable a visually impaired visitor, to relate to the object. Size in terms of the human body may be particularly useful, e.g. a London bus is five times the height of a person.

- Use the basic information found on a label, such as the name, title or subject of the object etc as a starting point before the description.

- A general overview of the object, which describes the object as a whole, can include subject matter if appropriate. Include the style of a work of art, or the context of an object. In a tour which includes descriptions of several objects, make comparisons between objects, styles and methods of production.

- To provide a starting point to the description of where objects are placed within the work, you might use the position of the numbers on a clock. For example, you may begin at the top of a painting, which would be 12 o’clock, and work down to the bottom of the picture, until you arrive at 6 o’clock.

- Do not skip around the object as this may confuse the visitor. Move in a logical, sequential order. Give accurate, precise instructions for moving from one place to the next. If you are working with a sculpture, work in a sequential movement, e.g. start from the head and move down to the feet.

- Once you have set the scene with a general description, fill in the gaps with specific details. Take time to show the relationship between details and the entire object.

- Take the lead from the visitor in when to finish a description. Dependant upon the interest or experience of the visitor will determine the length of time spent at an object.

Practical Art Workshops

The V&A offers more than just touch tours and audio descriptions with a planned series of workshop activities as part of the public programme. Providing practical activities allows visitors to express their own interpretation of the museum’s collection. The V&A has been proactive in providing events which are accessible to visually impaired visitors for many years.

In 1998, photographer Eric Richmond tutored a group of nine visually impaired people. They produced black and white pictures of the Sculpture Court which were displayed outside the V&A’s Canon Gallery of Photography. Participants reported that the course helped them to learn about photography and gave them greater access to the collections. Photography has been a favourite amongst visually impaired visitors with the museum running more than ten workshops since 1998.

Drawing and painting workshops for visually impaired visitors have also been popular. Terry and Lilly, who have never seen, were interested in Constable’s work. Using his sketches of the sky and light reflections on landscape, a series of raised drawings were produced and the pictures were described. They also found it of help to paint the sky themselves so that they formed a better understanding of how it continually moves and how Constable portrayed this. The Constable pictures and the raised drawings were displayed in the Constable Room at the museum.

Touch Me, a V&A exhibition held in 2005, explored the sense of touch both physically and emotionally. Visually impaired people participated in a workshop run by Carmel McElroy, designer of the Feeling Rug Knitted Fingers. Participants created their own rugs inspired by Carmel’s exhibited rug, giving their own interpretation on her work.

The most recent workshop focusing on the Constable and Turner paintings Seeing is Art, run by Sally Booth an artist who is herself visually impaired, taught visitors the techniques in which Constable and Turner created their work. Sally is now working with the museum to run regular workshop sessions focusing on other V&A collections including ceramics and photography.

Staff Training

To help achieve the work outlined above, the museum needs to have staff who wish to provide equality in service. The Disability Action Plan not only looked at the services, facilities and premises but challenged people’s attitudes: if you can’t get past the person on the door, it is pointless having an accessible environment.

The V&A has implemented training for staff to breakdown attitudinal barriers which prevent visually impaired people accessing the museum. Front of House and Learning Department staff received disability awareness training and visual awareness training, which I run.

Having a basic knowledge of the needs of the visitor and being able to ask the right questions “how can I help you?” aids a better customer service and more importantly takes the assumption of knowing how best to help the visitor without the knowledge base.

The Visual Awareness training is more than showing how to guide visually impaired people; a context of why we are doing such training is needed. Giving staff the background of visual impairment, facts and figures and dispelling some of the myths is important not only for their work at the museum but for life outside.

Safely guiding a visually impaired person around the museum is key to aiding an accessible visit. Therefore, some of the training is undertaken using blindfolds. This is not to show the person undertaking the task what it is like to be blind, it is to highlight how difficult it can be when Visually Impaired people visit an environment such as a busy museum. Being able to see the size of a room differs greatly to interpreting the space without sight and this task aims to highlight such factors.

Personal Experience

What is it like for someone who is visually impaired to work in the arts? Being blind and working on disability issues did not mean that I was the right person for the job. When I came into post, I was still studying the MSc Inclusive Environments Design and Management at the University of Reading. I had been working on disability issues since going blind in 1994 and the MSc was a way of formalising my experience with a qualification.

Like most people starting a new job, I wanted to make my mark, but in an organisation as complex as the V&A where do you start. Having little museum experience, combined with no interest in art, this role was going to be a challenge. I now have an interest in art, making it accessible to those who would like to access it and those who wish to work in the museum.

I have often been asked, “why are you working in an art museum if you don’t like art?” The reply is “the job I undertook was what made me apply”. The role encompasses every aspect of the V&A’s work, from the strategic planning to designing new galleries, developing policies and practices, staff training and managing the talks and events programme for disabled visitors, how often you get an opportunity to do so much variation in a job.

A lot of good work was happening at the museum on disability issues when I first came into post; however it was all isolated with no coherent approach, or often not known by others around the museum. To help the museum to take a coherent approach, I wrote the first Disability Action Plan as outlined above. Putting together my experience as an Access Consultant and studies at the University of Reading where I gained an auditing qualification, I audited the museum to find the levels of service or not as the case maybe.

I am not a person who likes to write lots of policies and then let them gather dust on a shelf; however, it is essential to write strategies and guidance which will lead to an outcome. The action plan was referenced to the Disability Discrimination Act, codes of practice produced by the Disability Rights Commission, Museums Libraries and Archive Council’s Disability Portfolios and my own experiences and ideas as an access auditor.

The Codes of Practice aimed to assist employers, service providers, premises owners and education providers on how to meet the Disability Discrimination Act, however they were long and often confusing as what would work for one disability wouldn’t work for another. With my interpretation of the Codes of Practice, the plan pulled together the positives and set out a plan of action for a three year period. The action plan was seen as best practice by the employers Forum on Disability in the 2006 Disability Standard, the first benchmarking survey on disability in the world. As this was the first Disability Action Plan I had personally written, it was pleasing to have gained such recognition but more importantly it was being implemented throughout the museum.

Any action plan isn’t worth the paper it is written on unless a budget is allocated to undertake the projects. After a short negotiation with the Finance Director who had some knowledge of access work, I walked out of his office with the best part of £100,000 ($160,000) increase in budget for year 1 projects. This budget gave me the opportunity to implement many projects, including:

- The instillation of a Fire Pager System which alerts deaf people to the fire alarm;

- Assistive technology on computers in the National Art Library and Prints and Drawings study room;

- The design and printing of the V&A’s first Access Guide.

One of the greatest challenges at the museum was getting people on-side as often people didn’t relate to disability or disability issues. Several colleagues felt that accessibility is just a whim, and as we haven’t had any disabled people come to the museum in the past, why should we make the building accessible. On one project, colleagues felt that if I spent the money on my proposal it would be “criminal” and “I was beating the museum with a stick”. Fortunately these people have now left the museum, with more open minded people in these significant positions.

Being at the right place at the right time is important when developing policies and practices which have long term implications. One of the practical changes made by the V&A’s Project team on FuturePlan was to include me into the design process. It is too late when your half way through a project to make changes as it becomes difficult to alter designs and becomes more costly. Since we have taken this approach, I feel access is more integrated and “we often get it right, more than we get it wrong”.

The V&A journey to accessibility has been long and difficult and sometimes sole destroying. The challenges which have been met and often overcome have led to improved accessibility for all visitors. I have found that access can be achieved even in organisations with complex structures; perseverance and a thick skin are key elements in the armoury of an Access Officer.

After ten years of work in the V&A, I feel I have learnt a grate deal, stretching myself on a daily basis. I hope I have shown colleagues that blind people can work and achieve their goals and access is for everyone to address and not just key individuals.

Copyright (c) 2013 Barry Ginley

Man steals $16,000 portrait from Santa Clara medical center

Man steals $16,000 portrait from Santa Clara medical center

According to the sheriff’s office, the suspect stole the piece of art from the new Sobrato Building at Valley Medical Center.

Anyone with information is urged to call detectives at (409)808-4500.

VENUE & EVENT TRENDS IN SAFETY AND SECURITY YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT

http://www.tsnn.com/venue-event-trends-safety-and-security-you-need-know-about

VENUE & EVENT TRENDS IN SAFETY AND SECURITY YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT

The Massachusetts Convention Center Authority’s Public Safety Team is actively preparing for the unexpected and developing strong working relationships with first responders. The team is a partner in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts’ Large Venue Security Initiative, along with Gillette Stadium, TD Garden, and Fenway Park, as well as FBI representatives in Boston, the Massachusetts State Police, the Boston Police Department, and more. Once every quarter, the group meets to review the trends and security issues that the event industry is facing.

Today, in the second installment of our emergency preparedness series, we are exploring some of these trends to help make your event safer.

Venue Trends

Most event venues are inviting and collaborative spaces, featuring a lot of glass and various pick-up and drop-off locations. These elements are now being reexamined and venues are moving towards hardening. There’s also more emphasis on traffic patterns, parking, and loading operations.

On the technology side, video surveillance and analytics, access control, and alert notifications are becoming a standard practice, especially for larger events.

Regarding crowd flow, venues are exploring ways to build a pedestrian flow into the building that goes through a traffic path but brings people through a level of security screening even when they don’t know it’s happening.

Event Trends & Security Tactics

As event professionals, we need to be extremely vigilant when we gather people and oftentimes, our job is namely to observe and report. This is where safety and security training, like the Suspicious Indicator Recognition & Assessment (SIRA) system, comes into play. SIRA incorporates many highly effective threat detection and mitigation protocols, allowing trained individuals to identify high-risk targets before an incident occurs. Having a trained staff extends your surveillance efforts to those at the ground level who are directly interacting with attendees. At the Boston Convention & Exhibition Center and the Hynes convention Center, all staff is required to attend a SIRA training session at least once a year.

In Boston, we have seen the real-life impact of attacks on mass gatherings firsthand. We know that the importance of safety and security planning has grown exponentially not only for meeting planners but for attendees as well. And when it comes to safety & security planning, it’ helpful to focus on event assessments and layered security.

At our facilities, we use a tier-based system to conduct event assessments and give the appropriate threat level (1-3) to each event. For example, a smaller event with a low risk can be a Level One, while an event with 40,000 attendees, extensive content, and public figures present might be categorized as a Level Three. Based on this assessment, our public safety team develops a customized strategy for each event.

Layered security utilizes different screening techniques and tactics to create security layers as attendees enter your event, but also within the event. For example, a keynote speech by a high-profile government official or celebrity may require an additional layer of security inside of your event for admittance. Those layers might be obvious (metal detectors, uniformed officers, and K-9s) or behind the scenes, such as undercover officers and camera surveillance.

As violent incidents become more and more common, it is easy to start thinking about them as something inevitable. But, there are many powerful tactics and techniques designed to help us mitigate our collective risk. The key is to stay informed and work with your venue partners to bring the appropriate level of protection to your events.